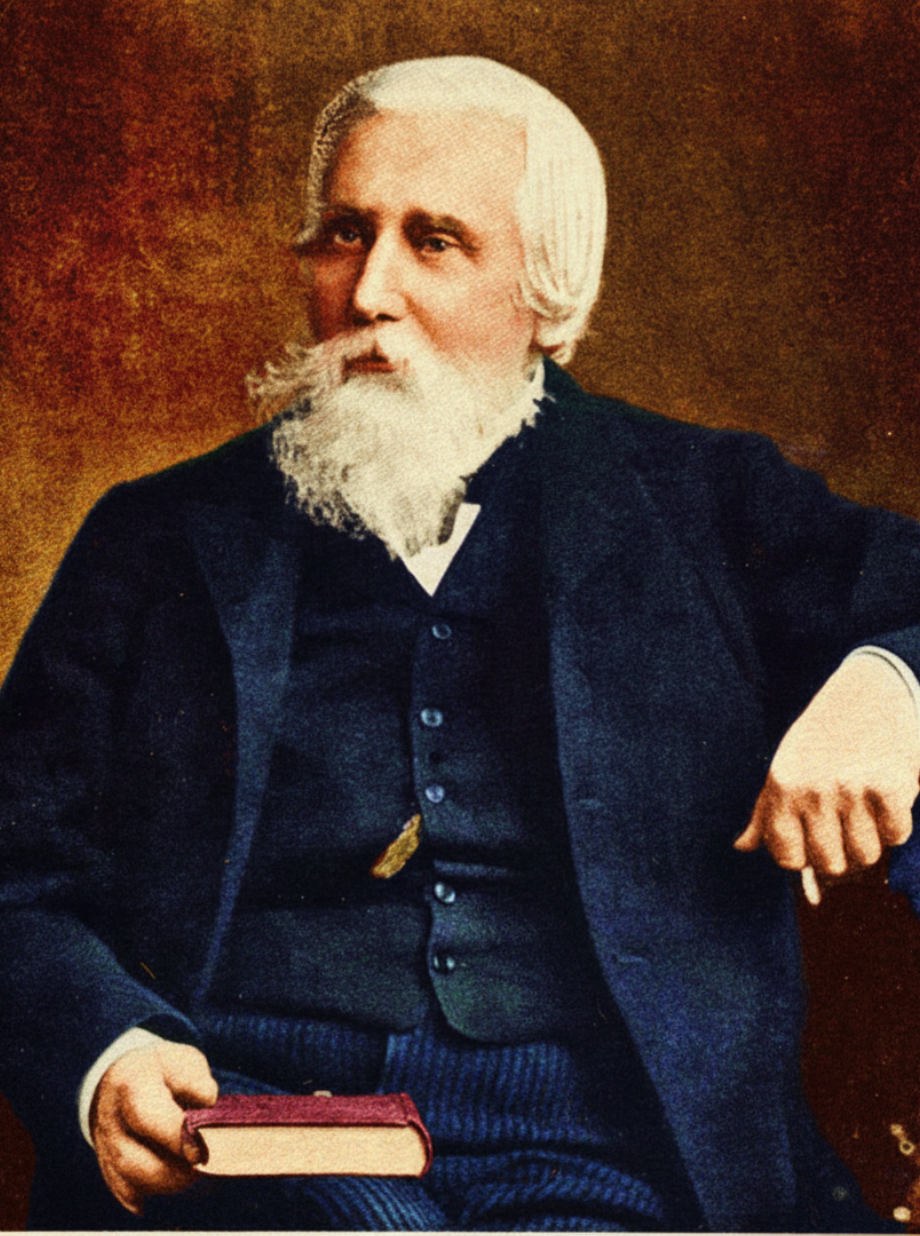

- Years of Life: 1827-1903

Early Life, Family, and Education

Clarence Esme Stuart was born in 1828 into a family of notable lineage and public distinction. He was the youngest son of William Stuart of Tempsford Hall, Sandy, and grandson of the Hon. William Stuart, Archbishop of Armagh, a man who, like his own father, enjoyed the personal confidence of King George III. Through collateral descent, the family traced its ancestry to the royal house of Stuart, and Clarence Stuart was by some thought to bear a physical likeness to Charles I. The Earl of Bute stood among his forebears, and his mother had served as maid-of-honour to Queen Adelaide, Duchess of Clarence, who became his godmother—hence the name Clarence. The name Esme itself carried strong historical associations familiar to students of Scottish history.

Educated first at Eton, Stuart proceeded, according to family tradition, to St John’s College, Cambridge. There he distinguished himself academically, taking his M.A. degree and winning one of the earliest Tyrwhitt University Scholarships in Hebrew, an achievement that revealed both linguistic aptitude and an early inclination toward sacred study. Under the godly influence of his mother, he had already experienced in youth the spiritual change described in Scripture as passing “from death unto life” (John 5:24).

Though it was expected that he would eventually take Holy Orders in the Church of England, a defect in speech prevented this course, and he remained formally a layman—though in learning, devotion, and service he was anything but such in the ordinary sense.

Early Christian Service and Transition to Brethren Fellowship

After marrying a daughter of Colonel Cunninghame of Ayrshire, Stuart settled in Reading, where for several years he engaged actively in Evangelical church work. At this stage of life, his efforts included strong support for the British and Foreign Bible Society, reflecting both his evangelical convictions and his love for the Scriptures.

Around 1860, his attention was drawn to the position and principles of those Christians commonly, though inaccurately, called “Plymouth Brethren.” In Reading, a large and influential gathering existed, prominently associated with William Henry Dorman, formerly a Congregational minister whose connection with brethren dated back to about 1840. Through Mr. Dorman’s ministry and influence, Stuart became convinced that his own churchmanship was untenable according to Scripture. Without prolonged hesitation, he took his place in the Reading fellowship, which for many years thereafter was closely identified with his name.

Association with J. N. Darby and Ecclesiastical Controversies

During the years 1864–1866, Stuart’s loyalty to John Nelson Darby was tested by controversy. Mr. Dorman opposed Darby’s teaching concerning certain sufferings of Christ described as non-atoning, connected with His association with Israel—placing these views on the same level as the earlier errors of B. W. Newton that had led to the division of 1848.

Stuart’s scholarly command of Hebrew usage proved decisive in forming his judgment. Unlike Mr. Dorman, who seceded from Darby’s fellowship, Stuart remained convinced that Darby’s position was sound and stood with him through the controversy.

Again, in 1881, when another disturbance arose among brethren with Darby’s involvement, Stuart remained steadfast. At Darby’s death in 1882, Stuart’s voice was among those raised at his interment. For three more years he continued in association with those who acknowledged Darby’s special leadership.

The Division of 1884–85 and Independent Ministry

In 1885, controversy arose over views held and expressed by Stuart himself, particularly regarding the standing of the children of God. Many regarded his teaching as inconsistent with traditional brethren doctrine. A searching division followed, one that tested hearts deeply. Some rallied to Stuart, seeing his views as a genuine advance in truth; others, though uncertain of his conclusions, judged that the difference did not justify separation. Nonetheless, division occurred, and from that point Stuart pursued a more independent course.

The remaining eighteen years of his life were marked by intense literary activity. He became a frequent contributor to the periodical Words in Season, alongside the publication of numerous books and pamphlets.

Literary and Doctrinal Contributions

Clarence Esme Stuart was among the most prolific and scholarly writers associated with the brethren movement. His works ranged over doctrine, prophecy, textual criticism, and devotional exposition. Among his earlier writings were:

-

Thoughts on the Sacrifices

-

Simple Papers on the Church of God

-

Atonement as Set Forth in the Old Testament

-

Textual Criticism of the New Testament for English Bible Students

-

A review of Robertson Smith’s Lectures, widely valued even among Anglican clergy

In textual criticism, Stuart aligned himself with Tregelles rather than Scrivener, holding firmly to verbal inspiration and textual exactness.

Later writings included Christian Standing and Condition, which provoked intense debate, followed by extensive papers on propitiation, in which he insisted—based on Old Testament typology—on the presentation of the blood after death as the act of propitiation par excellence. This placed him at variance with many brethren teachers who held that the Cross itself comprehensively covered the atoning work.

His later years saw a remarkable series of devotional expositions on:

-

The Gospels (Mark, Luke, John)

-

Acts of the Apostles

-

Romans and Hebrews

-

The Psalms (praised by Professor Cheyne)

He also wrote vigorously against the rise of Higher Criticism, notably in The Critics: Shall We Follow Them?, defending traditional views of Scripture while remaining conversant with contemporary scholarship, including the work of Professor Driver. His extensive personal library included rare and valuable works, among them a Complutensian Polyglot, later gifted to St John’s College.

Character, Influence, and Final Years

As a man, Clarence Esme Stuart was simple in demeanour, gracious in manner, and deeply kind to the poor among the flock. He delighted to share biblical light with them and was widely respected for his integrity, learning, and independence of judgment.

As an interpreter of Scripture, he adhered closely to the text itself, valuing verbal inspiration and refusing the authority of patristic tradition or modern philosophical speculation. He stood firmly within the broad body of recovered ecclesiastical and prophetic truth characteristic of the brethren, even when controversy isolated him.

He died in the early years of the twentieth century, leaving behind a vast body of written ministry. Though often controversial, he must be counted among those whose voices continue to speak through their writings—men who laboured not for popularity, but for faithfulness to the Word of God.

“Although dead, he yet speaketh.”